The Secret of Elite Athletes — Mindfulness Meditation Practice Changes Brain Responses

- Lillian Chang, AMFF

- Jan 17, 2025

- 5 min read

Athletes often experience panic or fear under the pressure of competition, while elite athletes are able to perform excellently under high pressure, showcasing the skills they've developed through training. What contributes to their successful performance?If we are not athletes, but want to tackle "stage fright syndrome" or performance anxiety in situations like exams, interviews, public speaking, or performances, are there similar secrets? This study today conducted a small investigation into our brains and uncovered some astonishing conclusions.

Mindfulness is the practice of focusing on the present moment without judgment, and several studies have shown that it can improve the brain's response to stress. For instance, research on Marine Corps personnel has shown that after receiving mindfulness training, they were better able to understand and respond to bodily signals, integrating the body’s internal state with goal-directed behavior. This, in turn, improved performance and resilience under stressful situations (Paulus et al., 2009; Johnson et al., 2014).

The study we focus on today A pilot study investigating changes in neural processing after mindfulness training in elite athletes, Hasse et al 2015 uses a breathing task to test how mindfulness training helps athletes. It explores how mindfulness affects brain regions like the insula and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which are related to emotion and cognitive control. Does mindfulness change in these brain areas contribute to improving the resilience of practitioners?

The research was conducted at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) Center for Functional MRI. The participants were seven athletes from the USA BMX cycling team who took part in a 7-week mindfulness training program. The program was structured as follows:

Module 1: Inhabiting Your Body (180 minutes)

Focusing attention on the body

Mindful awareness of the body; body scan practice

Research on interoception, optimal performance, and mindfulness

Experiential exercise: straw breathing

Home practice assignments

Module 2: Getting Out of Your Own Way and Letting Go (180 minutes)

Awareness of wandering thoughts and recognizing how “story” influences performance

Mindful movement; seated meditation

Research on the default mode network (DMN)

Experiential exercise: effort versus letting go

Home practice assignments

Module 3: Working with Difficulty (180 minutes)

Confronting avoidance in the face of difficulty by working with the body

Seated meditation focusing on difficulty; seated meditation focusing on letting go

Research on pain and negative emotions

Experiential exercise: ice bucket

Home practice assignments

Module 4: The Pitfalls of Perfectionism and the Glitch in Goals (180 minutes)

Identifying strengths and their “dark side”

Mindful walking, seated meditation

Research on perfectionism and self-criticism

Experiential exercise: compassionate inner coach

Home practice assignments

Last part: Six Weekly Foundational Practice Sessions (90 minutes each)

Group sharing

Discussion on practicing mindfulness during injury

Mindfulness practice

This was a 7-week intensive mindfulness training program, consisting of four core modules and six weekly follow-up practice sessions. The first two modules were focused over two consecutive days, with two 3-hour sessions each day, focusing on body awareness, mindfulness techniques, and strategies for dealing with challenges such as mental wandering. The third module teaches participants how to handle difficulty, stress, and pain through mindful interaction with the body, while the fourth module focuses on the downsides of perfectionism and self-criticism, emphasizing self-encouragement, self-love, and motivation. After completing the four core modules, participants attended six weekly 90-minute practice sessions where group feedback and discussions deepened their understanding and application of mindfulness practices. Additionally, participants were encouraged to practice mindfulness for at least 30 minutes daily, integrating it into their daily life and work environments to achieve optimal results.

After completing the training, the researchers collected data from the participants in three ways.

First, the BMX athletes underwent fMRI scans before and after the training and completed questionnaires to assess their personality and cognitive abilities. The questionnaires included:

Five Facets of Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ): This measures five key aspects of mindfulness: observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience, and non-reactivity to inner experience.

Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA): This is used to measure participants’ awareness and response to their bodily sensations.

Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS): This assesses the ability to identify and describe one's emotions.

Second, participants performed a breathing test. They wore a nose clip and used a special device in their mouth to perform one minute of restricted breathing. They rated their experience on how comfortable, unpleasant, and intense the breathing restriction was, using a scale ranging from "not at all" to "extremely."

Third, they underwent a Functional MRI Inspiratory Breathing Load (IBL) task. During the fMRI scan, participants performed a simple task where an arrow appeared on a colored rectangle, and they had to press a button to indicate the direction of the arrow. The color of the rectangle indicated whether they would experience a breathing load: blue meant "no load" and yellow meant there was a 25% chance of experiencing the load. The task was divided into four conditions: baseline (no load), anticipation (25% chance of load), breathing load (40 seconds of restricted breathing), and post-breathing load (response after the breathing load). The goal of this task was to study the participants' performance and brain responses to the sensory stimulus.

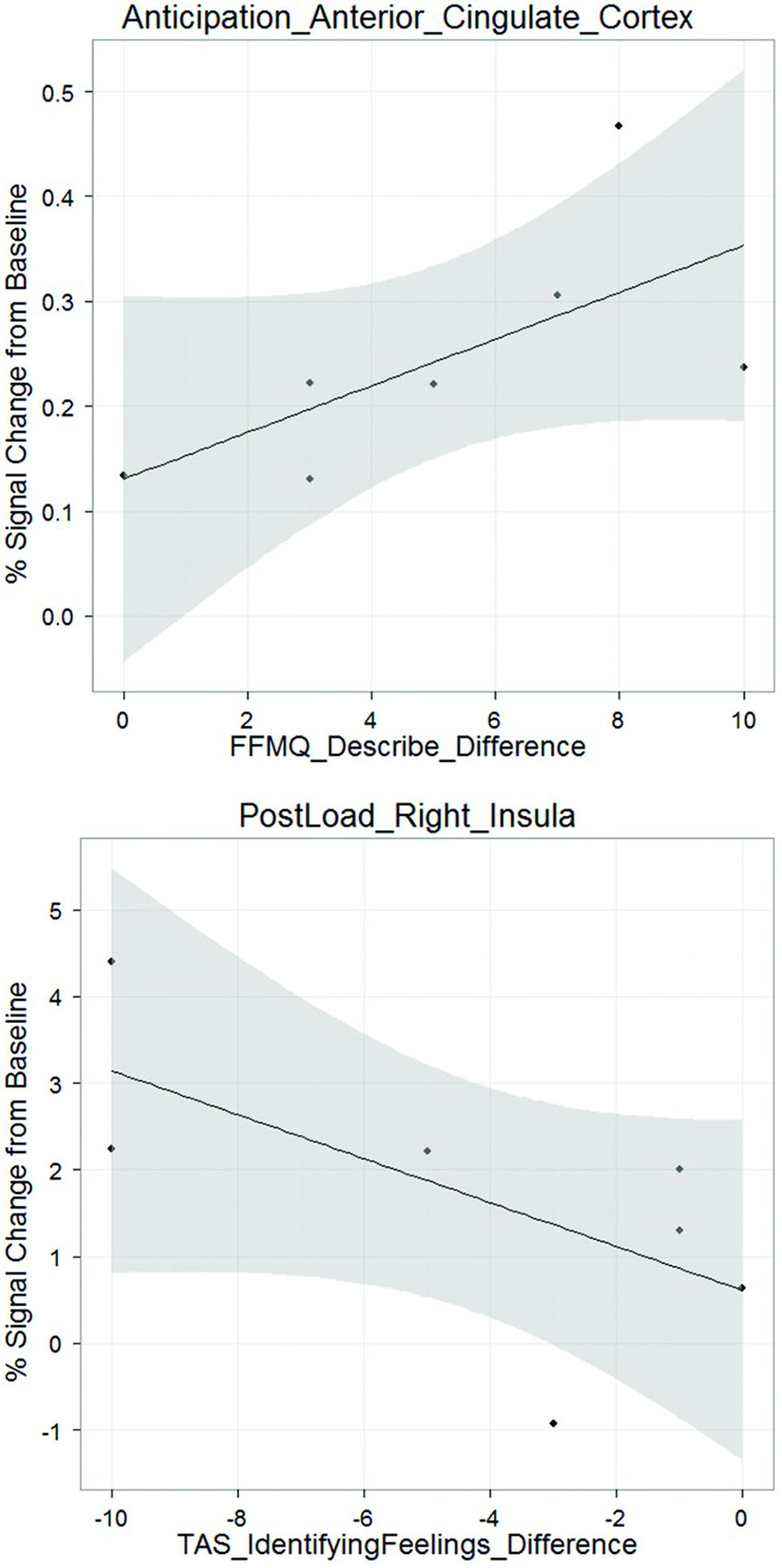

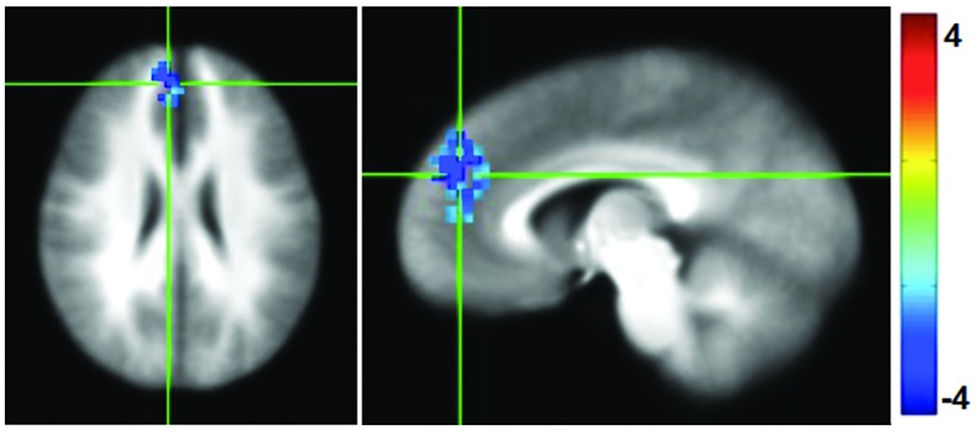

The training program primarily used mindfulness to enhance body awareness and improve the ability to respond to bodily signals, especially in stressful situations. The results showed that after seven weeks of intensive mindfulness training, the athletes had greater interoceptive awareness, stronger mindfulness, and improved emotional recognition skills. When facing the breathing load task, there was an increase in the activation of brain regions such as the insula and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). This means their self-regulation, resilience, and abilities to describe and identify emotions were all enhanced. The fMRI brain imaging results confirmed these improvements. The data showed increased activation in areas of the brain related to internal sensations, awareness, and cognition, such as the insula and ACC, which are primarily involved in processing bodily sensations and managing emotional responses. Additionally, their resting state functional connectivity (FC) between the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and other brain regions decreased, indicating an improved ability to switch between different brain networks responsible for cognitive control, thus helping to improve focus and emotional regulation.

In other words, mindfulness training helped the athletes activate key areas of their brains, enabling them to be more focused and aware of their bodily sensations and emotional responses during stressful situations (like during competitions). This allowed them to better recognize and regulate these physical and emotional reactions, aiding their resilience.

On the flip side, if these areas of the brain and body were not activated and enhanced, other regions associated with negative reactions—such as self-criticism, self-denial, and falling into negative emotions—would become more active, leading to common reactions like pre-competition panic, fear, or stage fright.

At the end of their published article, the researchers acknowledged some limitations of the study, such as the relatively small number of participants and the lack of a control group of athletes who did not undergo the mindfulness program. Despite these limitations, the study significantly contributes to our understanding of why mindfulness training helps athletes cope with stress, shedding light on the brain science behind it.

We often tell ourselves and our friends or loved ones before an exam, interview, or other important challenges, “Relax! You’ve got this!” We all know that this can feel like a hollow encouragement because it’s not so easy to relax under pressure! However, this study tells us that the physical reactions of nervousness, anxiety, and stage fright can be managed through brain training. Stress management is an integrated training that works from the brain to the body and emotions. And this kind of training likely isn’t something that can show immediate results just ten minutes before going on stage. Why not try a month of mindfulness meditation practice before a very important event? It may just cure the "stage fright syndrome" that has been troubling you for a lifetime.

©️Copyright: Please indicate the source 版权所有:转载请注明出处

Comments