How Meditation Reduced the Experience of Pain and Suffering

- Lillian Chang, AMFF

- Jan 15, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Jan 17, 2025

In ancient Eastern texts, the suffering, anxiety, stress, dissatisfaction, and frustration we encounter in life are analyzed and metaphorically described as two arrows. The feeling of pain in our lives can be caused by many intense or harmful events, but there is an essential difference between the pain we experience from these events and the pain we create in response to them. The pain we experience from intense spasms or the loss of a friend is different from the resistance or resentment we add on top of that pain. For example, we may respond with anger and blame, thinking "This shouldn't have happened to me, this isn't fair, a good person like me shouldn't be treated this way."

The Eastern text says that when an untrained mind is "struck by the sensation of pain, it will worry, be sad, grieve, beat its chest, cry, and become frantic." This is like being struck by two arrows: the first is the original arrow that causes the pain, and the second is the psychological pain that the person creates themselves. A practitioner with awareness, however, will only experience the sensation of pain—the first arrow—and will avoid the sting of the second arrow.

This describes two aspects of pain perception: one is the direct sensory experience, and the other is the habitual negative thinking that follows. The so-called "second arrow"—the negative psychological reaction after pain—can be eliminated through practice. This idea aligns with modern science, which has also proven that cognitive and emotional factors can greatly influence our experience of pain.

The study we are introducing today, A non-elaborative mental stance and decoupling of executive and pain-relatedcortices predicts low pain sensitivity in Zen meditators

Grant et al, 2010”explores whether meditation training can change the way people experience pain.

Pain is a complex experience that involves sensory, emotional, and cognitive aspects. Activity in the somatosensory cortex (SI, SII) and the thalamus (THAL) reflects the intensity of the pain felt, while the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and insula (INS) reflect the unpleasantness of pain. Activation in the prefrontal cortex is associated with the memory or evaluative process of the pain experience.

Previous research has shown that meditation can influence the emotional and cognitive processes related to pain, with some studies finding that meditators have lower pain sensitivity. Additionally, meditators’ brain gray matter morphology can change, including in areas associated with pain.

In this study, 9 advanced Zen meditators (male, mean age 38.8 years) and 9 non-meditators (male, mean age 37.6 years) were recruited. They were subjected to 24 brief (6-second) heat pain stimuli applied to their calves, while functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was used to collect and study brain activity. Participants also completed a questionnaire regarding their meditation practices.

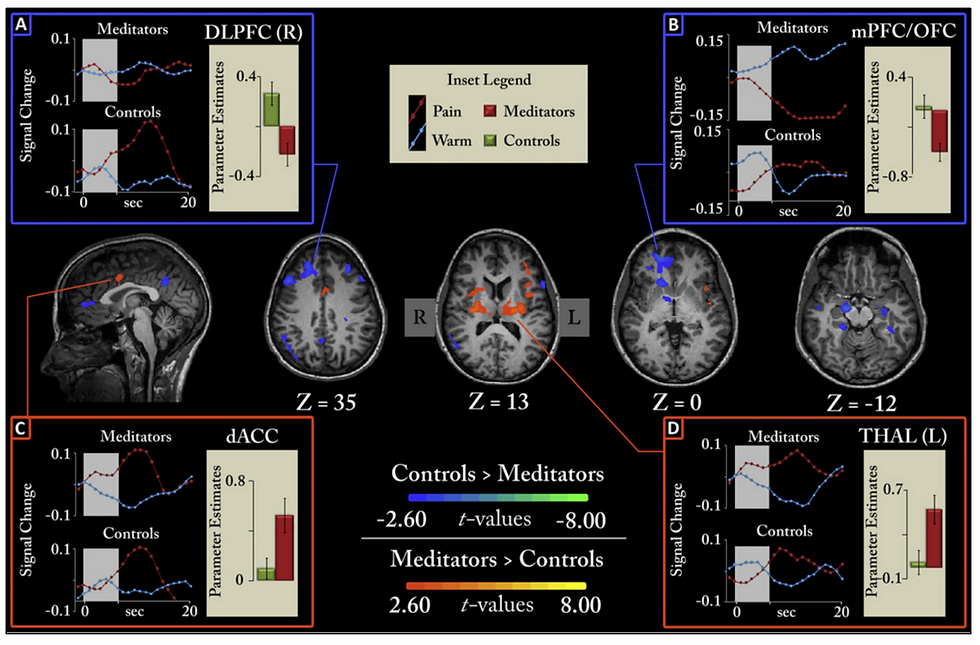

The results showed that, firstly, Zen meditators experienced moderate heat pain at 50°C, while non-meditators experienced it at 48°C. More importantly, when exposed to heat pain stimuli, Zen meditators exhibited: 1) Increased brain activity in areas related to pain sensation and emotion processing (such as the insula, thalamus, and anterior cingulate cortex (dACC)), showing stronger activation; 2) A reduction in connectivity between brain regions (such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and dACC), with significant decreases in activation in brain areas associated with pain evaluation and memory processing.

Let’s take a closer look at what the activation in these two brain regions means.

First, the significantly activated areas—the insular cortex (INS) and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC)—are part of the brain’s salience network, which is responsible for detecting important stimuli and responding to them. Therefore, the researchers suggest that Zen meditators, when experiencing pain, use stronger mental effort to sharply monitor the present experience. The higher their focus, the lower their perceived pain, so they report feeling less pain.

Second, the brain regions responsible for higher cognitive functions, such as evaluation and memory (like the DLPFC and dACC), show reduced connectivity and significantly decreased activation in Zen meditators. This enables meditators to process pain with lower cognitive effort. This aligns with the common attitudes of focus and non-judgment in meditation practices, and suggests that meditators' pain processing becomes more "neutral" or less threatening.

In other words, Zen meditators' brains become highly active in areas related to present-moment focus and monitoring sensory experience when they experience pain, while the cognitive regions of the brain become less active. Taken together, by sharply monitoring and focusing on the pain experience, and reducing cognitive evaluation of the pain, Zen meditators regulate their pain perception. This is consistent with the principle of non-judgmental awareness in Zen. In other words, Zen meditation may not directly reduce the sensation of pain but instead regulates it by altering the way pain is processed and perceived.

Now, let’s revisit the metaphor of the first arrow and second arrow that we discussed earlier. Which arrow does Zen meditation training help us deal with, or does it help with both?

This study suggests that Zen meditation primarily helps people apply the principle of non-judgmental awareness to perceive, observe, and even focus on the experience of pain without judgment, thereby reducing the second arrow—the additional emotional and psychological suffering that results from our reactions to pain.

Beyond this study, many other studies have also shown that meditators tend to have lower sensitivity to the first arrow, the immediate sensory experience of pain, or pain sensitivity.

However, what makes this study stand out is that it addresses something many people consider to be more controllable—the second arrow. The first arrow, the direct experience of pain, is often seen as less controllable in our lives, while the second arrow, the additional suffering we create through our reactions and emotions, is something we have more control over. Therefore, through the non-judgmental awareness practice in Zen meditation, we can better reduce the second arrow of suffering.

As mentioned earlier in the Eastern texts, the best way to reduce our suffering is through the healing power of the present moment—our ability to exist in the here and now, without any preconceived goals, maintaining a quiet and open mind, and cultivating a warm and caring heart. This way of being is often referred to as mindfulness. Thich Nhat Hanh compares mindfulness to the sun: whether the sun shines on a blooming flower in spring or a concrete building, it brings transformation.

©️Copyright: Please indicate the source 版权所有:转载请注明出处

Comments